It all started in the Burgundian War between 1474 and 1477. The armies of Charles the Bold of Burgundy suffered defeat after defeat by Swiss troops, despite being well-equipped and organized themselves.

The decisive difference was attributed to combat morale. The Swiss troops formed a militia made up of the local population, while the Burgundian troops were traditionally an army of landed nobles and levies—those who were less motivated to fight to the end. After all, every loss suffered by a noble who was there to fulfill his vassal obligation wasn’t compensated.

The decisive difference was attributed to combat morale. The Swiss troops formed a militia made up of the local population, while the Burgundian troops were traditionally an army of landed nobles and levies—those who were less motivated to fight to the end. After all, every loss suffered by a noble who was there to fulfill his vassal obligation wasn’t compensated.

In the end, Charles the Bold lost his life in the war. The next Burgundian ruler, Maximilian, who inherited the position through marriage, learned his lesson. After a quick skirmish with the French (who questioned his legitimacy), Maximilian decided he needed a standing professional army to protect his interests, just like the Swiss troops.

This army accompanied Maximilian until the end of his life, as he eventually became the next Holy Roman Emperor. Meanwhile, the army he created remained prominent in warfare for an entire century after his death. The name "Landsknechte" (singular: Landsknecht) originally comes from the words "länder" (earthly/local) and "knecht" (guard/servant).

Arms and Armour of the Landsknecht

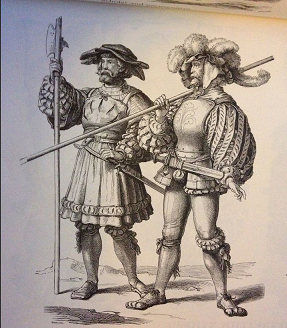

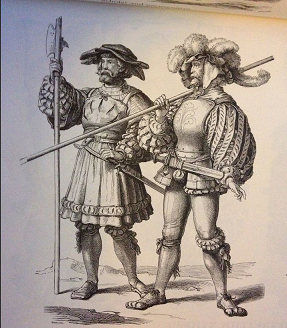

A single battalion was composed of 500 men. Fighting in a square formation, there were three kinds of armaments. The backbone of the formation was the spear. The vast majority of the unit—300 of them—were armed with spears. While the spears were a little shorter than the traditional spears of the Swiss mercenaries (Reisläufer) at the time, they required both hands to wield. Fighting with a stick that’s 14 feet long is not an easy feat, and you can't use any shields. Not that a shield would have saved you from a cavalry charge, but a wall of spears, on the other hand, made for excellent protection.Real veterans fought at the front of the formation, receiving double pay. They were armed with halberds and the famed two-handed greatsword, the zweihänder, in case someone got through the wall of spears. Spearmen, when too close to the enemy, could not defend themselves while holding the spear, nor could they dodge in the tight formation of their allies.

A single battalion was composed of 500 men. Fighting in a square formation, there were three kinds of armaments. The backbone of the formation was the spear. The vast majority of the unit—300 of them—were armed with spears. While the spears were a little shorter than the traditional spears of the Swiss mercenaries (Reisläufer) at the time, they required both hands to wield. Fighting with a stick that’s 14 feet long is not an easy feat, and you can't use any shields. Not that a shield would have saved you from a cavalry charge, but a wall of spears, on the other hand, made for excellent protection.Real veterans fought at the front of the formation, receiving double pay. They were armed with halberds and the famed two-handed greatsword, the zweihänder, in case someone got through the wall of spears. Spearmen, when too close to the enemy, could not defend themselves while holding the spear, nor could they dodge in the tight formation of their allies.

The halberd was a great weapon for keeping distance but could still cut through armor or use the hook on its back to drag a rider down. The greatsword was likewise good for close-quarters combat and against armor, but it also served the purpose of cutting down enemy spearmen. The spear is one of humanity's most ancient weapons, used before we mastered metals, meaning everyone who ever wanted to engage in war utilized it. Since modern combat discarded the shield in these formations, a weapon capable of cutting the spear shaft took its place. Well, that’s not entirely true—the buckler, a relatively small metal shield worn on the wrist, was developed. Shields were still useful, but having both hands free was better regarded.

The Doppelsöldner also had to make himself useful at range, equipped with an arquebus rifle, making it no longer an option for the enemy to simply wait out the formation at a safe distance from the spears. These soldiers were placed more towards the sides. In earlier times, most soldiers opted for the crossbow. Maximilian I abolished its use officially, but if needs must, crossbows would do almost as well. As time went on and gunpowder weapons became more developed, each formation started to have fewer pikemen and more riflemen. This was not a quick change though; we’re talking about a slow paradigm shift that took a century.

As a last resort, they also had a short sidearm, the Katzbalger. Having a shorter close-range weapon was great if the enemy got too close, or if you had lodged your halberd too deeply in someone’s helmet to recover it afterward.

Organization

We’ve already mentioned that a single battalion was 500 men. A proper regiment was composed of around 8 battalions (4,000 men), and an army could have multiple regiments. A regiment was led by a colonel, and beneath him were the captains. The colonel could also have his own personal staff, depending on how much he could afford: a doctor, chaplain, scribe, scout, quartermaster, eight bodyguards, and two musicians (a drummer and a fifer). In case you’re wondering, the music was for marching and signals. The captains could have had the same staff, but with additional musicians and only two bodyguards.

Lastly, there was the Provost. Law was crucial in any fighting body, and the Provost was the internal police. Disobedience, dereliction of duty, or theft met with swift punishment. He also had his own staff. Including a jailor, executioner, and bailiff.

The Landsknecht recruited people from every social class. There were young nobles who would never have inherited no land, destitute citizens who couldn’t learn crafts, artisans who were ousted from their guilds, criminals who had to flee their homes from the law, and so on.

They weren’t simple feudal levies. They were beholden to no singular lord or tied to a specific piece of land. Landsknechts went where there was conflict and pay to take part in said conflict. If they received no pay, they abandoned the fight and/or took their due via looting. Of course, when there was no work to be done, they also became the most dangerous bandits of the land. However, as long as they had a lord giving them legitimacy, they could fight anywhere.

A single battalion was composed of 500 men. Fighting in a square formation, there were three kinds of armaments. The backbone of the formation was the spear. The vast majority of the unit—300 of them—were armed with spears. While the spears were a little shorter than the traditional spears of the Swiss mercenaries (Reisläufer) at the time, they required both hands to wield. Fighting with a stick that’s 14 feet long is not an easy feat, and you can't use any shields. Not that a shield would have saved you from a cavalry charge, but a wall of spears, on the other hand, made for excellent protection.Real veterans fought at the front of the formation, receiving double pay. They were armed with halberds and the famed

A single battalion was composed of 500 men. Fighting in a square formation, there were three kinds of armaments. The backbone of the formation was the spear. The vast majority of the unit—300 of them—were armed with spears. While the spears were a little shorter than the traditional spears of the Swiss mercenaries (Reisläufer) at the time, they required both hands to wield. Fighting with a stick that’s 14 feet long is not an easy feat, and you can't use any shields. Not that a shield would have saved you from a cavalry charge, but a wall of spears, on the other hand, made for excellent protection.Real veterans fought at the front of the formation, receiving double pay. They were armed with halberds and the famed